As many of you already know, my goal is to build a longevity-focused biotech company. A few months ago, I decided it was time to dive deep into biology – and what better way than by getting into the lab and learning genetic engineering hands-on?

Genesis

Since I was in the Bay Area at the time, attending Vitalist Bay, I signed up for the Biopunk Lab, a sort of “WeWork for lab space” in San Francisco (or an open community lab, to be more precise).

(I missed the chance to join the MIT How to Grow Almost Anything (HTGAA) course, but I highly recommend it to anyone looking to start on this path!)

The first step was deciding what exactly I wanted to do. I knew I wanted to focus on longevity science, so I narrowed all my ideas to that field.

Initially, I was planning to get started with mammalian cells, since that would be the closest I could get to working with the human body. I was planning to do a knockout of the p16INK4a gene, which plays a role in senescence – a tried-and-tested protocol I could use for learning.

Working with bacteria vs mammalian cells

Seeing the high prices for basic materials to start with mammalian cells was shocking. Cell lines start at ~$300, and FBS (a common growth medium) ranges from $200 to $400 per 500 mL. So I reached out to scientist friends to see if anyone had extras (they can subculture certain cells to grow more). I couldn’t find HEK293 (the go-to beginner line), but I did get access to some myoblasts, mouse neural tissue, and fibroblasts!

(One friend even had his own biopsy-derived cells to spare, but warned me they were not great for senescence experiments, as they were sourced from a 43 y.o. (himself) lol)

However, since I had just over a month left in SF (stupid v!sas 🙁 ) and it was my first time in a lab, my mentors strongly advised that I start with bacteria (or yeast!) instead.

Why? Because working with mammalian cells takes muuuuch longer, is waaaay more expensive, and the risk of error (a.k.a. killing the very expensive cells you have been working on for weeks) is much, much higher.

In contrast, you can get bacterial cultures for ~$10 USD, and the media costs just a few bucks. They’re relatively resilient and easy to work with, and you can potentially keep culturing them semi-indefinitely.

I will say I was kind of bummed! Bacteria don’t really share our longevity pathways (yeast do, btw!!!), so they’re a terrible model to learn about human aging. Still, bacteria are excellent for beginners to learn about genetic engineering.

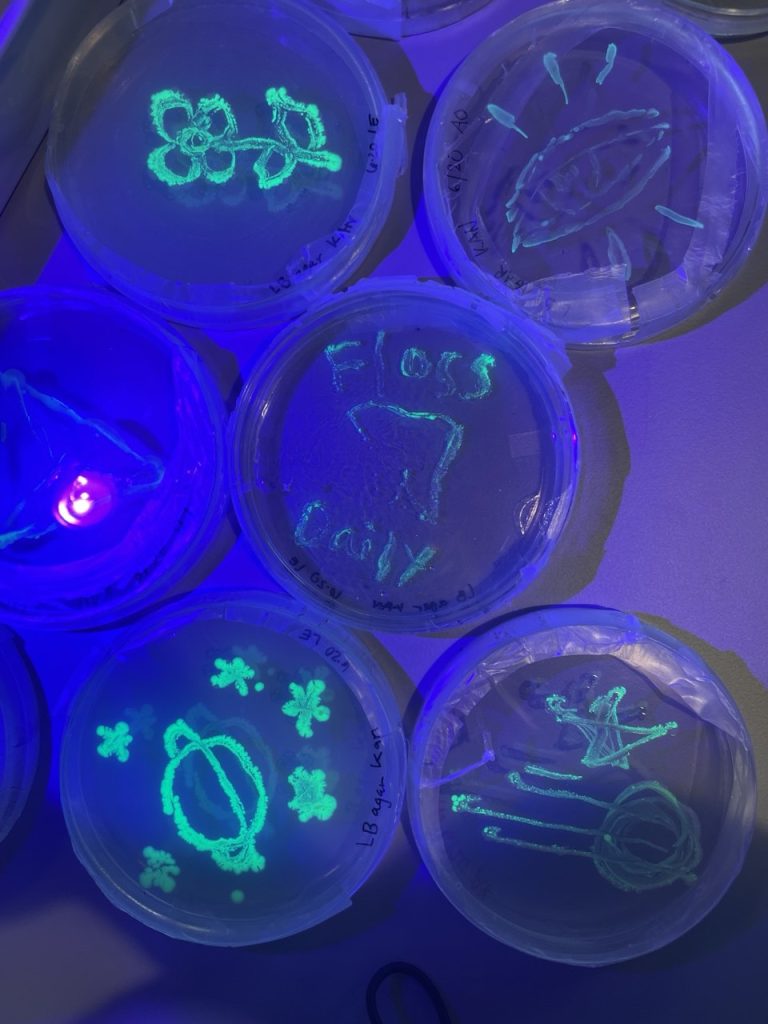

I wanted to stick to longevity, so I decided to make bacteria overexpress spermidine, which is a compound that has shown some longevity benefits.

(Bacteria, like us, naturally make this compound. The plan was to genetically engineer them to produce more, then extract and isolate it.)

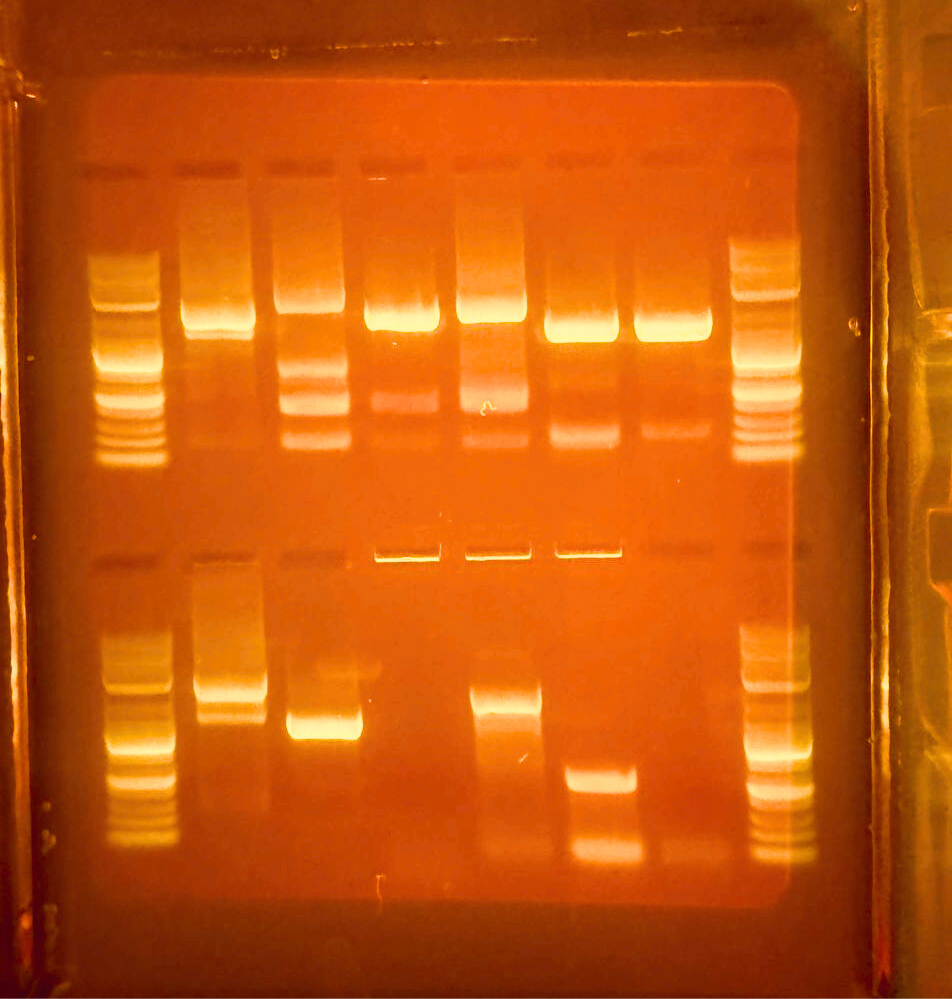

Throughout this process, I learned about plasmids, primers, CRISPR, PCR, gel electrophoresis, Golden Gate/Gibson assembly, and miniprepping – plus basics like culturing and cloning.

In lay terms: how to design DNA edits, modify plasmids (DNA modules that change bacterial “behavior”), get them into bacteria, and isolate, measure, and replicate DNA.

(I also learned a few other techniques from shadowing others, like magnetic bead-based DNA purification from watching Keoni make grape-flavored bread)

On learning solo

I went through this process mostly solo (relying on chatGPT/LLMs and Youtube videos), with occasional help from mentors, but I REALLY REALLY REALLY recommend that you try to get some mentors to help you at the beginning. Even shadowing them for a bit can make a big difference, especially if you’re self-training.

My journey was made somewhat smoother thanks to having some mentor support, but it was much bumpier than it would have been if I had consistent help. Having someone supervising or guiding me when doing things for the first time would have saved me a lot of time and mistakes (I wasted a TON of time at the beginning being confused and unsure about how to proceed).

In biology, mistakes can be very time-costly, as frequently you will not realize that you have F’d up until hours, days, or sometimes even weeks later (hours/days if in bacteria, hence why it’s recommended for beginners).

TLDR: Try to find a mentor for a few sessions or sign up for a few classes before you start, if you can.

I used ChatGPT a lot (I also recommend Perplexity if you want to verify sources), and found YouTube tutorials and LabXchange super helpful.

Is it pointless to learn wet lab in 2025?

Many people were puzzled by my decision to start learning lab skills in 2025, given the risk for automation. To be clear, I am doing this to deepen my understanding of biology, so I can be a competent founder who knows their field. After all, there will always be value in learning by doing.

A brief pause

Unfortunately, I had to pause my training when I travelled to Europe, since I didn’t have access to a lab in my hometown in Spain 🙁 stupid v!sas

(I considered interning at a local university lab, but we all know how slow academic bureaucracy can be…)

I reached out to my network and Twitter to find a lab in Europe to continue my explorations, and luckily connected with a friend of a friend (now a friend!) who has a private lab space with BSL-2 facilities in London (and who doesn’t mind me doing my thing there).

(BTW people keep asking me “what’s that lab?” but it’s not an academic lab, and I am not officially affiliated with them – they are just very kindly letting me use part of the space!)

Where I’m At Now

My next step is to find the ONE experiment/area to focus on next. This sounds simple, but it’s actually a major bottleneck. Since I’m doing this independently (without a lab covering my costs), this decision matters a lot: each potential experiment requires different materials, which are expensive, making it hard to pivot later on.

My funding constraints limit my options significantly, since I need to prioritize experiments that use materials I already have or can get at minimal cost.

Additionally, once I start working on it, it’s a race against the clock. You need a very detailed protocol laid out in advance that you must execute diligently, as biology is very time-sensitive. (ie you have limited time windows before cultures die, media degrades, and countless other time-sensitive scenarios.)

Finding my next project

While my main interest is in gene therapy, I’m hesitant to commit to one niche too soon. Given what I have access to, I’ll likely explore reprogramming (if I can do it for cheap!) and iPSC, although I don’t plan to start a company in that space since it seems oversaturated.

My criteria for picking a project:

- High potential impact (measured in QALYs/DALYs)

- Bonus points if I could bring it to humans in 5-10 years

- Accessible for a small startup

- Doesn’t require highly specialized & expensive equipment

- $5-10k to get early data (excluding what I already have); $50-100k for a PoC

- Not overcrowded

I’ll prioritize the candidates with the greatest scaling potential and the most futuristic/transhumanistic angle, since feeling like I’m helping shape the future is what most fuels me 🙂

Other roadblocks + joining a lab?

As I mentioned, I am mostly doing this alone. I have been warned that getting results with more advanced experiments without proper prior training is * very very * difficult, so I am kind of worried that I will waste a ton of money on failed experiments with nothing to show by the end. (Although I have at least 1 mentor specialized in gene therapies who can help me on the weekends!)

I am also aware that not having a biology background or official experience at a biotech lab/startup can hinder my chances of success as a biotech founder.

For both of these reasons, I am considering interning at a lab where I can maximally speed up my learning around seasoned mentors and peers.

(I am exploring an option in Shenzhen, but LMK if you know of other opportunities that could be a good fit!)

How to help!

If you made it this far and relate to my journey, here’s how you can help:

- If you are an experienced lab scientist, reach out for:

- Mentoring

- Spare materials you can share (if near me)

- Cool lab opportunities!

- If you have experience with non-academic grants (think Emergent Ventures), I’d love your advice on unlocking funding.

- Any helpful opportunities for the O-1 visa.

(If you’d be down to pitch in some $$ for lab materials, or contribute $1-2k to the upcoming Aevitas House microgrants program to fund other people’s promising proof-of-concepts, DM!)

To follow my journey, follow me on X/Twitter, or subscribe to my blog Accelerating Utopia.

Special thanks to Elliot Roth, Keoni Gandall & Sebastian Cocioba for the mentoring and putting up with my n00b questions and random pings 😀

Thank you for your initial guidance when I was getting started on this journey: Alex Plesa, Michael Florea, Omri Amirav-Drory, Alexandra Stolzing, Mark Hamalainen, John Schloendorn. And thanks to Priya Makhijani & Taylor Valentino for the Buck Institute tour + my first mammalian cell shadowing experience!